Letter from my Grandfather's WWII Squadron to my Dad on his First Birthday

So my grandfather was a B-25 pilot in WWII. He died over there only seeing my father in person, one time through glass at the hospital. After my dad's death, I found a letter his squadron wrote to my dad on his first birthday about his dad. I've transcribed it and thought I'd share here. It's pretty interesting; some off-putting characterizations of the Japanese, but I guess that's war for you. Mostly just an interesting snap shot into history and a glimpse at a close family member I never knew.

________________

THIS IS A LETTER TO MIKE

FROM HIS DAD'S SQUADRON

July 28, 1944

Dear Mike,

This is a funny sort of letter, Mike, a sort of time letter. Because you're only a year old today, and I guess when you can actually read it yourself, this war, and all that is important to us today, will be dim recollections and something for the historians to puzzle about.

You've probably heard a lot of stories about your father. About what a pilot he was; about his West Point schooling; about his low-level missions against the Japanese in the Marshall Islands. I guess your mother has told you a lot of things about "Ted" - told you about how he looked at you through a glass in the hospital just before he took off for overseas; about how she sent ted pictures of you, in fifty different poses and moods, with notations on the borders; about how he acted and what he did.

But she couldn't tell you very much about what we, in his squadron, thought of him. You see, he was our Old Man, too. We lived with him for many, many months, in training and in combat. We knew him differently from the way your mother knew him, or his parent knew him. We knew him as our commanding officer -- and as our friend.

I guess, outside of your mother and you, Mike, Ted loved flying more than anything in the world. He was already a pilot, with hundreds of hours in the air, when he filled out a personal form for the Army. One of the questions was: "What is your hobby?" Know what he put down? "Aviation." One time I asked him what type of airplane he liked best. He grinned at me and said: "All of 'em."

You know, there wasn't a man who flew with him, or a man who flew on the same missions with him, who didn't think he was just about the best pilot in the business. He was good, too. He did things in his Mitchell B-25 that most pilots wouldn't even think of, much less attempt. And he pulled his plane out of some scrapes that even he admitted later: "I didn't think I was going to get out of."

I asked him, only a couple of weeks before he died, what his biggest thrill was, during his Army career.

"I guess the first combat mission I went on," he said. "I flew with Scraggs (a pilot of another squadron) as his co-pilot -- I wanted to see what these low level missions were all about. Well, I found out. We hit Maloelap all right, and we sunk a Jap destroyer and got all tangled up with a lot of Zeroes. We got ourselves shot up a bit, too, on that one.

"But every mission is exciting. When you're turning onto that bomb run, it just can't help being exciting."

Mostly, though, he always described a mission as "the fun we had." When one was 'rough', or he went chasing around low level, looking for targets for his 75 cannon, or just strafing, he used to say: "We had a lot of fun on that one."

He was a real professional soldier, Mike. He was given a job to do, and he was doing it to the best of his ability. His squadron's job was to neutralize the atolls in the Marshalls, and later Ponape and Nauru. And he just figured out the best way to carry ou that assignment.

First time his squadron had orders to go on a detached service up on a little coral base in the Marshalls, to strike Ponape, Ted called his squadron together for their first briefing.

"We have an island full of Japs," he said, "And they're all ours for the next two weeks. Let's go get them."

We always though the Colonel was pretty much of a fatalist. I'd never heard him mention the word "death" -- he always said "lost", or "went down" -- he never said "killed." At a briefing before a mission, for instance, he'd say: "Don't bunch up too closely because if you do, there'll be an awful mess up there" or "I don't want the planes too close together and when we turn into our run have any collisions" or "don't follow directly in the path of your lead plane -- you're apt to get his bombs in you lap."

But he wasn't hard Mike, or callous. He never mentioned the word "hate" or "revenge." It was just that war happened to be his job -- and Ted was a man to do his job as well and as efficiently as he could.

It was a funny thing, too, about the change in him. The men, that is, the enlisted men, didn't rate the Colonel any too highly when he was group operations officer. It seems he was curt and short, and, from all external appearance, as though he didn't care very much what peoples' attitude was.

But when he went over to the squadron, as C. O., he changed. Right away he began worrying about everybody in his squadron. He fought for the "rates" of his men, and all the little things that make the difference between living fairly comfortable out here on an atoll, and living in misery.

You know why? Well, we figure that when he was operations officer, he couldn't fly. And that's all he wanted to do -- fly. He was only human, Mike, and he couldn't help his own disappointment showing in his attitude toward others, Certainly, he did his job, and well. But he wasn't happy.

When he became squadron C. O., and could lead his planes, and his men. - well, inside of a month, Mike, he was the most popular C. O. in the group. And as his fame as a pilot spread, and his "rating" with his men rose, why the whole Air Force knew the Colonel was one swell man to be under. When one enlisted man brags to another about his Old Man, Mike, that man is tops.

A lot of fliers -- and a great deal more "paddlefeet" thought the Colonel was sticking his neck out the way he'd buzz a field, or stay around a target, strafing and shooting his cannon and turning and coming back and doing it again. They said he was just 'flak happy' and needlessly exposing himself and his crew.

But when I talked with him about it, I could see he wasn't. He was cautious and careful as the next men -- he knew, Mike, with a professional knowledge, like a boxer who knows his opponent, just how far he could go, just what moves he could make.

There was one time when he went over Ponape with two other planes on orders from the Navy to get some pictures of AA positions. He only had his navigator (Lt. McGir) and co-pilot (Capt. Colley) and photographer (Lt. Tingwall) with him.

Just as the were making a run over their target, at least 20 Zeroes jumped the flight. It lasted for 45 minutes and the officers in the Colonel's plane got plenty of machine gun practice keeping those Zeroes at a respectful distance. The other two planes, with trained gunners, got four Jap fighters sure and one probably out of the 20.

"We never would have gone in unprotected like that if we had any idea Zeroes would attack us," he said, later. "I was sure happy to get out of that one."

"But," he added -- and you could see just what he thought of the Japs as aviators -- "With all their advantage, they'd only come in for a few bursts and then bank away from us."

That is what I meant by "professional," Mike. He hated poor flying and he couldn't tolerate a man not dong his job; The Japs weren't doing their job and he had no respect for them. That's why he seemingly took so many chances -- he'd weighed the Japs and found them wanting and his calculations proved right -- the Colonel wasn't shot down, Mike.

There were times over the Marshalls when Ted went on one plane assaults that must have made the Japs think he was a miracle man. He banked through radio towers and telephone poles and literally jammed the nose of his plane right into gun emplacements and let go with his 75 cannon. When the squadron had a target assigned them to obliterate, the Colonel wanted to be damn sure it was obliterated -- that's the kind of soldier he was, Mike.

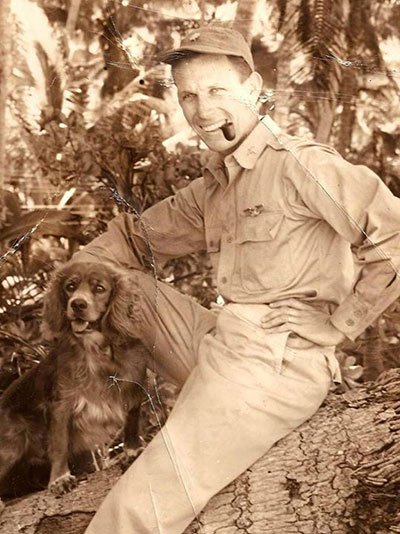

Then there was "Pistol Head" -- you've probably got a number of newspaper clippings about him. He made 47 missions with his Boss, Mike -- low level and medium level. He use to curl up right behind the flight deck, or, in a "D", he would wander back and forth between there and the nose.

For a week after the Colonel died, Pistol Head went around the area like crazy, Mike. He couldn't understand, and nobody could tell him. But dogs are pretty smart. One day he came over to the Colonel's tent, looked around and couldn't find Ted. Then, I think he realized what had happened. I think he knew then that the Boss wasn't coming back.

And I think he knew, maybe even better than we did, how the Colonel himself would have felt about the whole thing. Because Pistol Head took up his life again, like a man who had won a terrific battle with the odds all against him, and from that day on, Pistol acted the same as he had before. Only he never flew on a mission again. He was a "paddlefoot". I think Pistol knew that's the way his Boss wanted it.

There's not much more I can say, Mike. At the funeral, the whole squadron, to a man, turned out to give him military -- and personal honors. Just about everybody, officers and enlisted men, from the entire group, were in the background, not quite believing what the saw and what they knew to have happened. It just didn't seem possible. But in war, Mike -- or any life, for that matter -- anything's possible. We suffered a loss that was irreplaceable, but a few days later, we took off on another mission and the routine continued.